Who Cares About Free Speech? – Findings from a Global Survey

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

|

Support for free speech varies across the globe. Among the 33 countries surveyed, Scandinavians and Americans are most supportive while Russians, Muslim-majority nations, and the least socio-economically developed nations express the lowest levels of support. |

|

In Egypt, Hungary, the Philippines, Russia, Turkey, and Venezuela, the actual level of freedom of expression is very low compared to the popular demand for free speech. |

|

Support for free speech is generally expressed by great majorities in all countries when people are asked their opinion. |

|

However, when confronted with controversial statements – e.g., statements offensive to minorities or religions, supportive of homosexual relationships, or insults to the national flag, the support is generally lower and varies much more between countries and across issues and individuals. Likewise, variation between countries increases and the rankings are different when people are confronted with potential trade-offs regarding information that might be sensitive to national security, harm economic stability, or undermine the handling of epidemics. |

|

General support for free speech has not decreased since 2015. Most nations demonstrate stable or even increased levels of support. However, there are exceptions. Most notably, the acceptance of unrestricted criticism of the government has declined in the US. |

|

Individual background conditions in the form of gender, age, education, and placement on a left-right spectrum are related to support for free speech in different ways in different countries. There are some general tendencies, however, including higher tolerance among left-leaning individuals regarding insults to national symbols and more acceptance among right-leaning individuals of statements offensive to minority groups – particularly, in Western countries. |

|

In the US, young people, women, the less educated, and Biden voters are generally less supportive of free speech. |

|

In many countries, people have a tendency to understate tolerance of statements that criticize their own religion and beliefs. At the same time, many citizens have a tendency to exaggerate how important they consider the right to criticize their governments. |

|

In all the countries surveyed, a majority prefers some kind of regulation of social media content. However, only a few want the government to take sole responsibility for this. People in two-thirds of the countries surveyed favor such regulation to be carried out by social media companies themselves while a plurality in the rest prefer social media companies along with national governments to be responsible for regulating the content. |

|

Opinions about the regulation of social media content are sensitive to whether the issue is linked to statements about fake news or the repression of free speech. |

The right to freedom of expression is recognized under international human rights law and by almost all national constitutions as a fundamental right. Free speech is important for personal autonomy, and it is instrumental for the protection of other rights, including popular sovereignty, and for the progress of knowledge and human development. In the words of former Secretary-General of the UN, Ban Ki-moon, and the Director-General of UNESCO, Irina Bokova, “freedom of opinion and expression … are essential to democracy, transparency, accountability and the rule of law. They are vital for human dignity, social progress and inclusive development.”

Against this backdrop, it is disheartening that different independent organizations have reported a decline in respect for freedom of expression in recent years caused by overt as well as covert attacks by intolerant groups and governments. Most recently, the Covid-19 crisis seems to have augmented the problem. From 2012 to 2020, 32 countries experienced significant decline in respect for freedom of expression, while only twelve improved their status. But to what extent do ordinary citizens in different nations support the principle of free speech? This report seeks to answer this question based on data from representative surveys of individuals from 33 countries around the world. The surveys were developed by Justitia and implemented by YouGov and some of its international partners in February 2021 (see Appendix for details, including the specific formulation of questions).

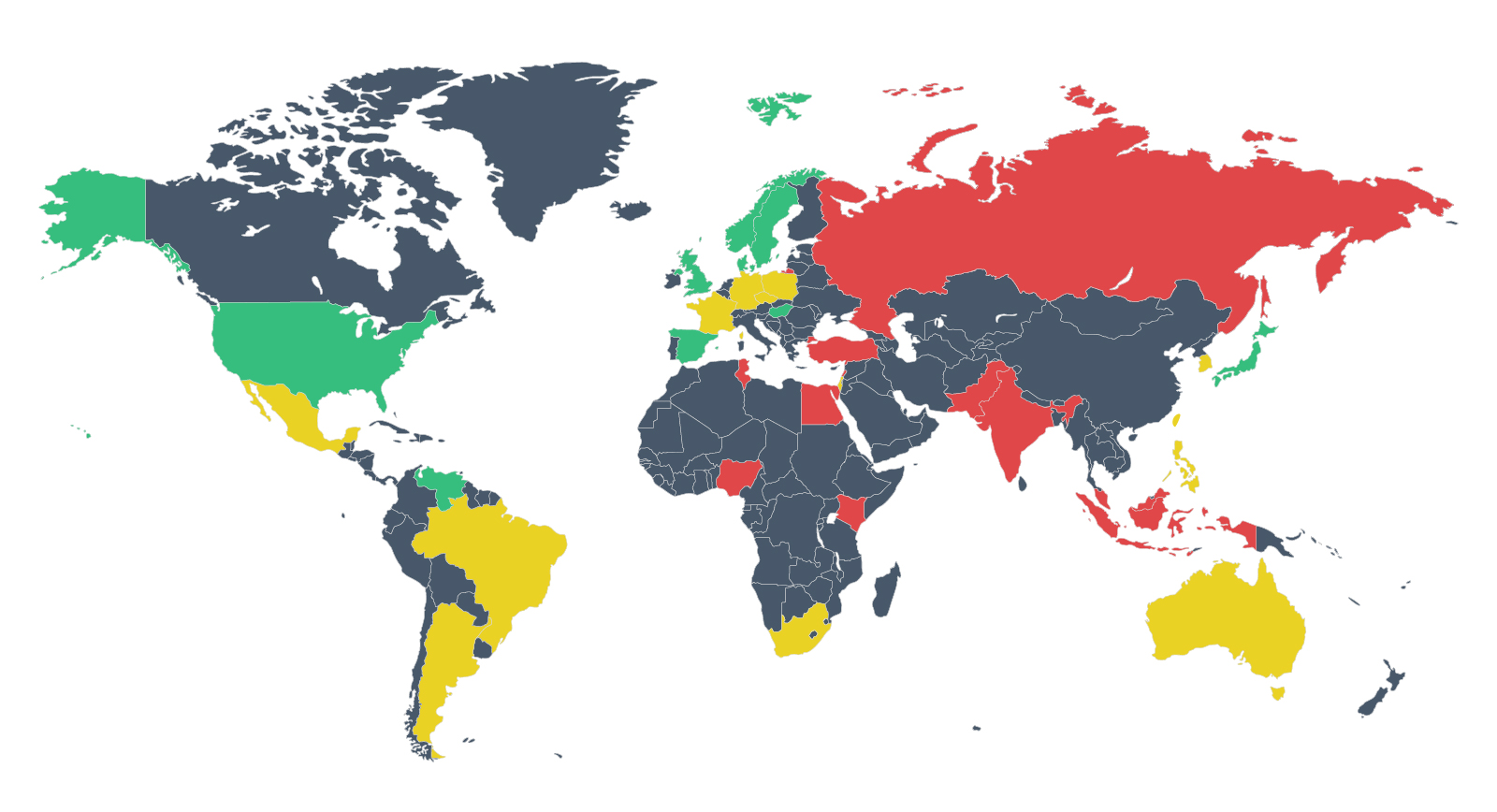

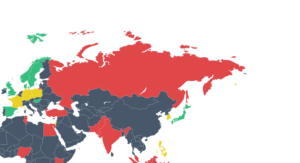

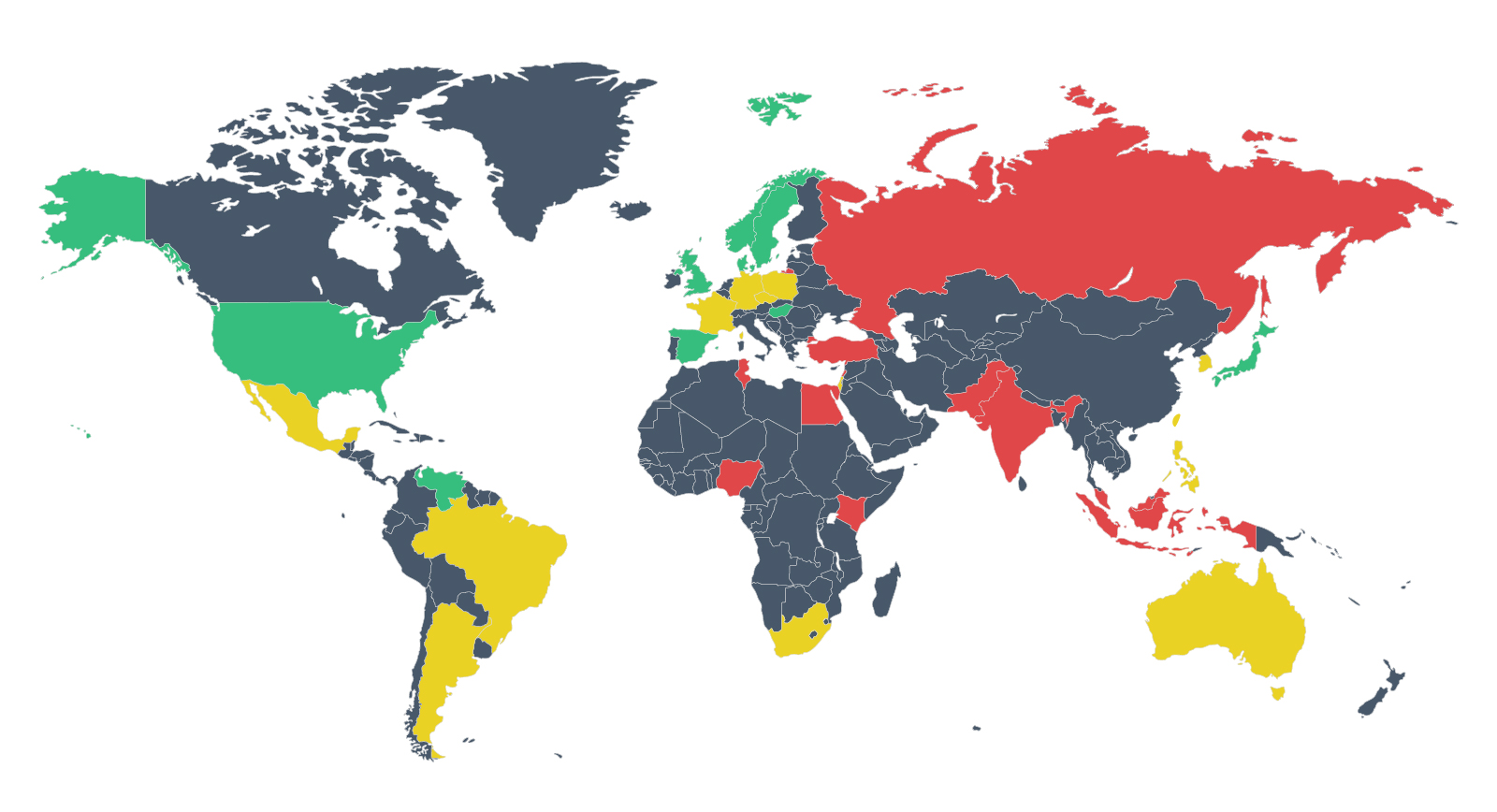

We have constructed a composite measure, the Justitia Free Speech Index, to assess the overall support for free speech in different countries. It is based on answers to eight questions about the willingness to allow controversial types of speech, such as the ability to offend religion and minority groups and to publish information that could destabilize the national economy. The overview reveals that people living in the Western world generally show more support of free speech than elsewhere. This finding is in line with previous studies.

Justitia Free Speech Index

The index is based on answers to eight questions about the willingness to allow controversial types of speech, such as the ability to offend religion and minority groups and to publish information that could destabilize the national economy

Scandinavians and Americans are most supportive while citizens in Latin America, other parts of Europe, as well as Australia, Israel, and the East Asian democracies (Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan) also show relatively strong support. At the same time, support for free speech is weaker in Russia, Turkey, other parts of Asia, and Africa. Egypt, Kenya, Pakistan, Malaysia, and Tunisia receive the lowest scores on our index.

When we match the Justitia Free Speech Index scores with country scores from V-Dem’s Freedom of Expression Index, there is a clear, positive association (the Pearson correlation coefficient is 0.55). This means that public opinion about free speech (popular demand) tends to go hand-in-hand with the actual enjoyment of this right (government supply).

In other words, nations more supportive of free speech tend to enjoy more freedom of expression in practice and vice versa. Pakistan, Malaysia, and India score relatively low on both support and practice. By contrast, the Scandinavian and Anglosphere (i.e., Australia, the UK, and the US) countries are at the upper end of the scale on both accounts. There are noteworthy exceptions to this pattern, however, as indicated by the countries placed far above and far below the regression line. Kenya, Tunisia, and Nigeria achieve relatively high values on the V-Dem measure, reflecting a relatively high actual enjoyment of the right, even though the popular support for free speech is relatively low. By contrast, Egypt, Turkey, Russia, the Philippines, Venezuela, and Hungary represent cases in which the popular demand for free speech is relatively high compared to how little the citizens may actually exercise freedom of expression without being sanctioned.

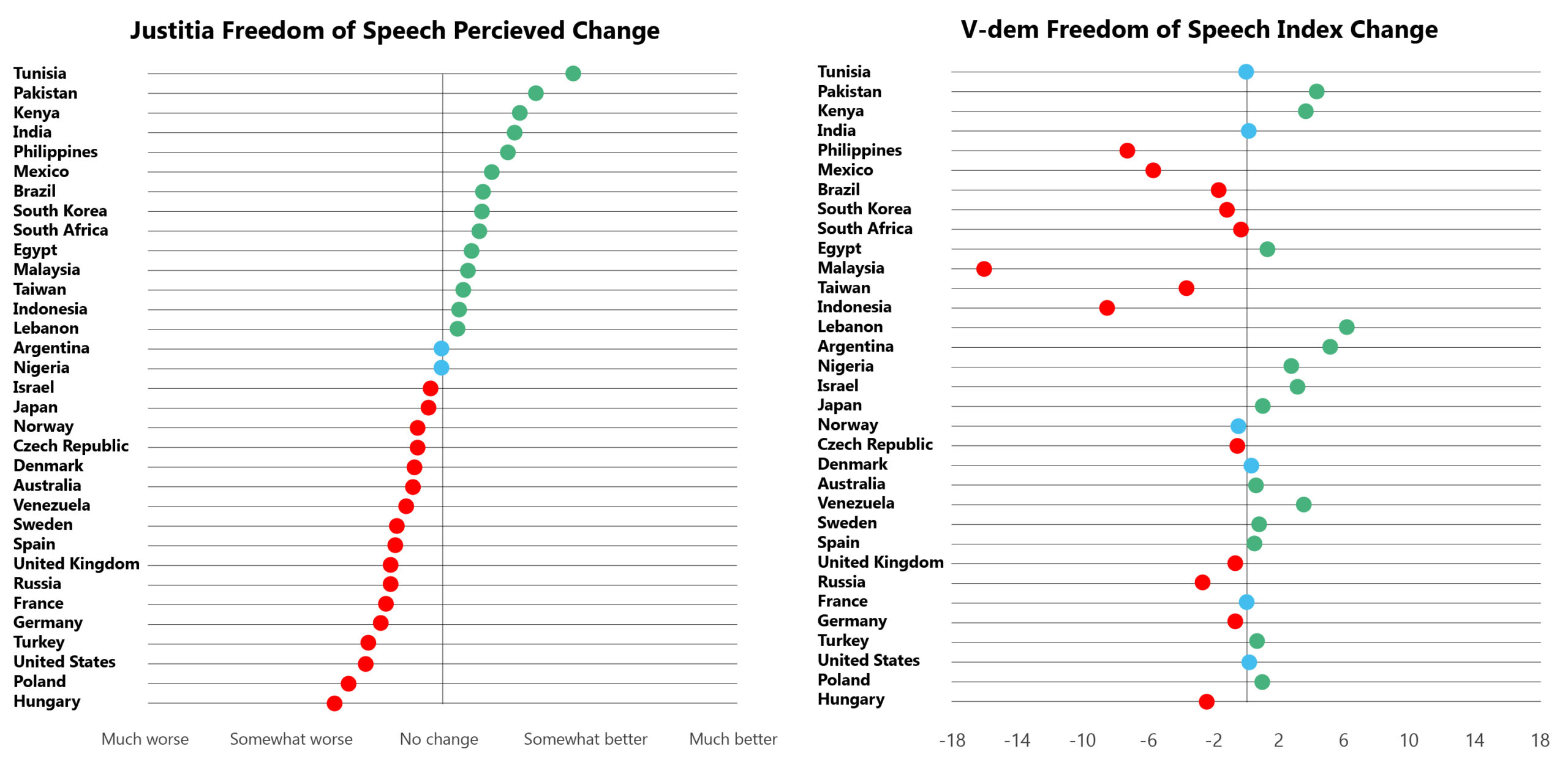

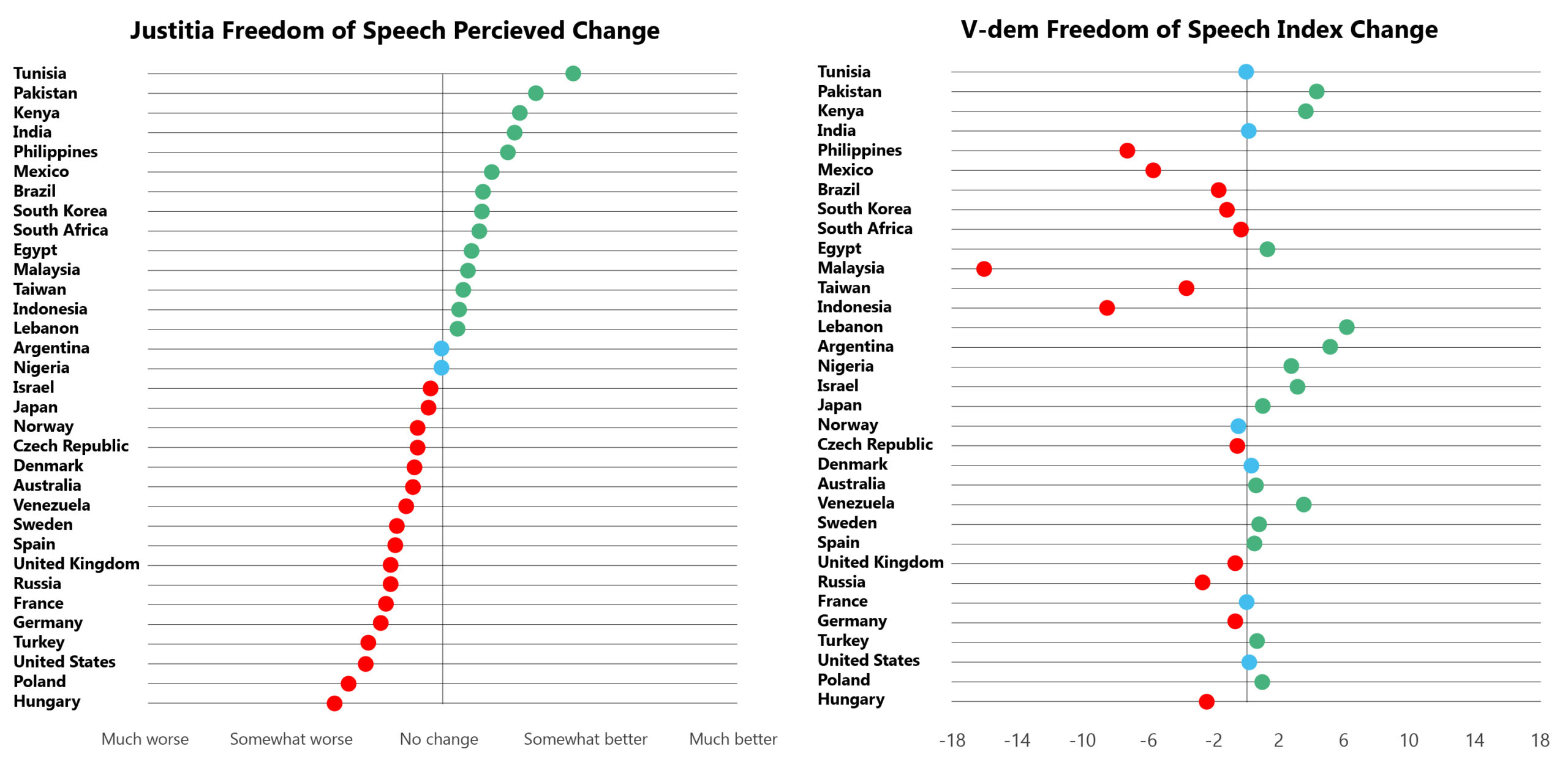

We do not have sufficiently detailed data to do a robust assessment of whether the Covid-19 pandemic has increased such mismatches between demand and supply. Nonetheless, when we ask people whether they think their ability to speak freely about political matters has improved or worsened over the last year, there are roughly as many countries in which the citizens believe that freedom of expression has declined over the last year as the opposite.

Tunisians, Pakistanis, and Kenyans state that they have experienced witnessed the greatest improvements. It is more surprising to see that, given recent democratic backsliding, citizens in the Philippines and India also think the conditions for free speech have improved. By contrast, Hungarians, Poles, Americans, and Turks believe that, on average, their right to free speech has decreased the most. These are all polarized countries in which incumbents have been intolerant of free and independent media both before and during the pandemic. However, many German and French citizens also feel that the situation has worsened substantially in their respective countries.

Perceived changes in ability to speak freely over the last year and changes in V-Dem Freedom of Expression Index from 2019 to 2020

The changes in V-Dem’s Freedom of Expression Index from 2019 to 2020 do not indicate a uniform decline during the Covid-19 crisis. Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Mexico represent the largest negative changes, whereas Lebanon, Argentina, Pakistan, and Kenya have apparently improved their performance. Most countries in the sample did not experience a significant change.

Finally, there is not much agreement between the perceptions of ordinary citizens and experts regarding recent developments. This is interesting since it puts into question the ability of either ordinary people or experts (or both) to make valid judgements about factual trends in freedom of expression. However, one has to take into account that the periods assessed are not exactly the same. The V-Dem assessment covers a calendar year, and our surveys were carried out in February.

The rest of this report provides an overview of responses to the many specific questions in the survey. It is divided into six sections, focusing on different but related themes. Section 1 shows the level of support for free speech when people are asked directly without being confronted with moral dilemmas or potential trade-offs. Section 2 reveals how, on average, respondents in different nations respond when they are asked about more specific types of free speech and particular trade-offs. Section 3 demonstrates how much support for free speech has changed in particular countries from 2015 to today. Section 4 disaggregates the responses and shows how support for free speech in selected countries varies across groups defined by age, education, gender, and political orientation. Section 5 follows up on the disaggregate perspective with a special focus on group differences in support for different types of free speech in the US. Section 6 presents the results from two list experiments, which shed new light on when and where there is a tendency to under- or over-report opposition to free speech. Section 7 shows how widespread support for regulation of social media content is and whom people think should be allowed to regulate it – if anyone.