|

About Counterspeech

Much public discourse around the world has become polarized and poisonous, especially online. To solve this, some countries have tried to use law, but criminalizing speech does not prevent it from causing harm, especially in the limitless, borderless digital sphere. Neither does the content moderation practiced by private social media companies, though they remove millions of posts every day for violations of law and their own internal rules. There is another method for improving discourse that has largely escaped attention so far: grassroots counterspeech. It deserves more attention and study. After all, more than law or law enforcement, group norms have the greatest impact on offline human speech and behavior: the unwritten but powerful rules with which communities govern one another.

Norms of behavior have always been taught and enforced in countless unrecorded conversations, mainly by individuals who know their audiences personally – parents, teachers, classmates, clergy, neighbors – not governments, companies, or other institutions. This does not work quite the same way online, since the internet has changed human communication in vital, relevant ways: 1) people can speak and behave without the same social constraints as they feel offline; 2) strangers, including very diverse ones, communicate with one another far more than ever before; and 3) online conversations are often recorded, and can be studied.

Communication on most social media platforms is regulated by the companies that own and operate the platforms, and, to a much lesser extent by governments that try to compel the companies to suppress certain forms of speech. These top-down forms of control have so far dominated policy discussions about how to improve online discourse. Meanwhile, however, thousands of people have quietly taken it upon themselves to counterspeak online: to attempt to enforce their discourse norms by responding to content they find hateful, harmful, or offensive.

The DSP searches for the best responses to harmful content, especially content that increases the risk of intergroup violence, which it calls dangerous speech. Several years ago, they noticed some counterspeakers at work. The team began searching for more, and gradually found many more.

Some operate alone, and many counterspeak together in well-coordinated groups numbering in the thousands. Theirs are true grassroots efforts: all the counterspeakers have taken it on voluntarily, without pay.

The DSP has studied them and their efforts, producing the first ethnographic study of counterspeakers, a detailed paper on what they are trying to accomplish, and a review of research on what impact they are actually having. In general, their goals are quite similar, and their techniques are strikingly different. From all this work, which is the largest body of research on counterspeech in the world as far as we know, the DSP has created the content for this toolkit.

Counterspeech is the practice of responding to speech that seems harmful or offensive. It can take many forms such as challenging, debunking, or critiquing harmful speech, amplifying alternative viewpoints, providing accurate information, and fostering empathy and understanding. Organizations and researchers use different definitions of counterspeech. The following are representative examples.

- The Dangerous Speech Project defines counterspeech as “any direct response to hateful or harmful speech that seeks to undermine it.” The DSP distinguishes counterspeech from counternarrative, which means offering a view contrary to another one, without responding to any particular content, so a feminist essay would be counternarrative to misogyny, for example.

- The Council of Europe similarly distinguishes counterspeech from counternarrative, which it calls “alternative speech.” According to the Council, “while counterspeech is a short and direct reaction to hateful messages, alternative speech usually does not challenge or directly refer to hate speech but instead changes the frame of the discussion.”

- Nadine Strossen, a civil liberties advocate and former president of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), a venerable U.S. advocacy organization, considers counternarrative to be a form of counterspeech. She has described counterspeech as “a shorthand term for any speech that seeks to counter or reduce the potential adverse impacts of hate speech or other controversial speech. A major form of counterspeech is education or information that counters the ideas and attitudes that the problematic speech reflects.”

- The Mannerheim League for Child Welfare writes that “counter-speech is the opposite of hate speech.” “Counter-speech is humane, empathetic expression. The purpose of counter-speech is to show that every person is valuable. In everyday situations, counter-speech means standing by the target of discrimination.”

- Counterspeech scholars Joshua Garland and his colleagues define it as “a form of citizen-based response to hateful content to discourage it, stop it, or provide support for the victim by, for example, pointing out logical flaws in the hateful comment or using facts to counteract misinformation.”

Though these definitions differ, they all describe counterspeech as a response to hateful speech, meant to decrease its harmful effects. The variations among definitions are also important. Scholars and practitioners disagree about whether counterspeech is always civil, for instance. Some maintain that it is, such as the Mannerheim League for Child Welfare which defines it as “humane, empathetic expression,” but most definitions do not include such a qualification. Another difference is whether the definitions are narrow (requiring some link between the original speech and the response) or broad (lumping the categories of counterspeech and counternarrative/alternative speech together).

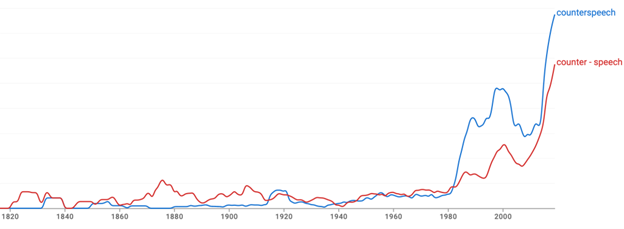

Responding to offensive speech is not new – people have long, in one way or another, expressed their disagreement with comments that they find harmful. But the concept of counterspeech as a response to hatred is relatively recent.

“Counterspeech” (also spelled “counter-speech”) appeared in print at least as far back as the early 1800s, although in all of the early cases, the term meant simply a refutation of any speech (not necessarily hateful or harmful texts). For example:

- “Speech and counterspeech did not fit into each other. The speakers spoke over one another’s heads” (Written in 1918 in The Independent Vol. 95, a weekly magazine published in New York City between 1848 and 1928.)

- “For the first of them contains three speeches upon love, one of Lysias in favour of the position that a boy should bestow his favour upon a cold and dispassionate lover rather than an enraptured and impassioned one, and two of Socrates – the first a supplementary speech, in the same sense in which such speeches were usual in courts of justice to defend the same cause with the preceding; the other, on the contrary, a counterspeech in favour of the impassioned suitor so severely accused in the first.” (From Schleiermacher’s Introductions to the Dialogues of Plato. 1836). The contemporary notion of counterspeech is much more recent, and as illustrated in the figure below, the term has become much more common in recent years.

Figure from Google Books Ngram Viewer – usage of terms in English language books from 1820-2019

In the United States, the concept of counterspeech is often traced back to U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis D. Brandeis, who wrote in a famous 1927 opinion that replying to harmful speech, not censoring it, is the best response. Though he joined the rest of the Court in upholding the conviction of a California woman who had helped establish the Communist Labor Party of America, Brandeis declared:

“If there be time to expose through discussion the falsehood and fallacies, to avert the evil by the processes of education, the remedy to be applied is more speech, not enforced silence.”

U.S. lawyers often call this the counterspeech doctrine, though Brandeis never used the term. Based on it and other related ideas, the Supreme Court has interpreted the U.S. Constitution’s freedom of expression provision very broadly, making it the most speech-protective national law in the world.

A counternarrative is a perspective or story that challenges or opposes another view of a particular topic, issue, or event. It presents an alternative interpretation, analysis, or understanding of historical events, social issues, cultural norms, or political ideologies.

Counternarratives are often developed by marginalized groups or individuals who challenge prevailing ideas or beliefs that support stereotypes, oppression, or exclusion. They aim to provide a voice to those who are often unheard or misrepresented in mainstream narratives. Counternarrative campaigns are also frequently used to challenge extremism.

Sometimes the campaigns are produced by NGOs or governments, and they take the form of short videos, ads, or even video games designed to go viral within the target audience. Average Mohamed, a series of animated videos about a Somali immigrant living in the United States, created by an NGO with the same name, is a good example of this kind of counternarrative effort. The title is also the name of the main character of the videos, which challenge propaganda used by extremist groups such as ISIS to indoctrinate and recruit Muslim youth.

Other counternarratives are shared through grassroot campaigns, often on social media around a common hashtag. One example of this type of response is the #MyFriend campaign, launched in 2015 by Burmese activist and former political prisoner Wai Wai Nu. Dangerous speech targeting Muslims in Myanmar— especially on social media — has received attention from scholars and human rights practitioners, and in 2018, United Nations investigators said that social media played a “determining role” in the campaign of crimes against humanity and genocide in which the Myanmar military killed more than 10,000 Rohingya Muslims.

The #myfriend campaign encouraged Burmese people to post selfies with friends of different religions and ethnicities along with the hashtags #myfriend and #friendshiphasnoboundaries with the goal of reducing “all forms of discrimination, hatred, hate speech, and extreme racism based on religion, ethnicity, nationality, color and gender” in Myanmar and encouraging “love and friendship” between groups. In Myanmar during this time, directly speaking out against the government meant risking prison or worse. The #myfriend campaign was a subtle but clear rejection of messages teaching that Rohingya Muslims were a threat to Myanmar and its Buddhist majority.

The Future of Free Speech Project

The Future of Free Speech Project (FFS) was launched in 2020 by Danish think tank Justitia and, since 2023, is a collaboration between Justitia and Vanderbilt University.

The Value of Free Speech

Free speech is the bulwark of liberty; without it, no free and democratic society has ever been established or thrived. Free expression has been the basis of unprecedented scientific, social and political progress that has benefitted individuals, communities, nations and humanity itself. Millions of people derive protection, knowledge and essential meaning from the right to challenge power, question orthodoxy, expose corruption and address oppression, bigotry and hatred.

At the FFS we believe that a robust and resilient culture of free speech must be the foundation for the future of any free, democratic society. We believe that, even as rapid technological change brings new challenges and threats, free speech must continue to serve as an essential ideal and a fundamental right for all people, regardless of race, ethnicity, religion, nationality, sexual orientation, gender or social standing.

The Global Free Speech Recession

Free speech has been in global decline for more than a decade. Left unchecked, this deterioration of free speech threatens individual freedom, civil society and democratic institutions as well as progress in science and philosophy. There are many reasons for the global decline in free speech, including the rise of authoritarianism on all continents. Even in open societies, the democratization and virality of online speech are increasingly seen as a threat rather than a precondition for well-functioning, free, tolerant and pluralist societies. Threats – both real and imagined – from hate speech, extremism, terrorism and disinformation have led to calls for stricter regulation of speech from both authoritarian and democratic governments, social media companies, individuals, and NGOs. To mention just one example, the recent coronavirus has led not only to a global public health emergency but also to a global censorship pandemic, as many governments scramble to suppress misinformation, while others have used the opportunity to grab even more power over both the press and online opinions. Such measures put both the value of and the right to free speech under pressure but also challenge defenders of free speech to reexamine, update and upgrade the arguments for why free speech matters. Historical lessons are crucial to understanding the value of free speech, but in a digital age, in which propaganda and disinformation can travel the globe in seconds, it is no longer enough to rely solely on tried and tested free speech arguments from previous eras.

What we do

To understand better and counter the decline of free speech, the FFS seeks to answer three big questions: Why is freedom of speech in global decline? How can we better understand and conceptualize the benefits and harms of free speech? And how can we create a resilient global culture of free speech that benefits everyone? The objectives are to understand better why we need free speech and to explain better why the freedom to speak is so fundamental. We will also extrapolate how we can protect free speech while addressing legitimate concerns surrounding misinformation, extremism, and hate speech.

To do this, we pursue a three-part endeavor: (1) Through polling and research, we will measure global attitudes toward free speech and analyze whether common concerns and arguments used to justify restrictions of free speech are based on real or imagined harms. (2) through defending and strengthening existing standards needed to resist the global authoritarian deterioration of freedom of expression. (3) Through outreach, the FFS provides activists, policymakers, academics, and other critical stakeholders with the data, arguments, and standards to help turn the tide of what the FFS calls the free speech recession.

Ultimately, the FFS aims to generate knowledge and spark the involvement needed to energize activists, persuade skeptics, resist authoritarians, and foster a resilient global culture of free speech.

The Dangerous Speech Project

The Dangerous Speech Project is a nonpartisan, nonprofit research team studying dangerous speech: any form of communication that can increase the risk that one group of people will violently turn against another group. We try to find the best ways to counter this, while also protecting freedom of expression. We are not part of a university or any other institution.

Our Mission

We envision a world free of violence inspired by dangerous speech, in which people also fully enjoy freedom of expression. We equip people to counter dangerous speech and the violence it catalyzes, through research, education, and policy work.

What We Do

The DSP works primarily in five areas:

- Studying, and developing useful ideas about, dangerous speech and its harms

We gather and analyze historical and current examples of dangerous speech from around the world, to better understand the link between speech and violence. Drawing on this research, we have written a detailed practical guide for identifying and countering dangerous speech, online and offline. Our FAQ provides quick insights as well.

Through our fellowship program, we have commissioned detailed case studies and data sets of dangerous speech from researchers in many countries, since such analysis is best done by people who are fluent in the relevant languages and cultures.

- Investigating and evaluating responses to dangerous and other harmful speech including hate speech

To diminish the effects of dangerous speech and other forms of harmful expression, we study the wide variety of methods, many of them creative and contrarian, that people and civil society organizations have developed to respond to such speech in constructive ways, including counterspeech. We have brought many of these pathbreakers together for the first time, both privately and publicly, which has both informed our research and overall work.

- Adapting, framing and disseminating dangerous speech ideas for use by key communities.

As much as we can, we deliver our ideas to people who can use them to study dangerous speech and counter it. In addition to making our publications widely accessible, we also conduct trainings and workshops for a variety of groups including activists, educators, lawyers, researchers, students, and tech company staff. As a result of these and other efforts, our work has been used to study and/or counter dangerous speech in countries as varied as Nigeria, Sri Lanka, Denmark, Hungary, Kenya, Pakistan, and the United States.

- Advising and critiquing decision makers on speech governance

As experts on ways in which speech engenders violence, we use our research to advise the tech industry on how to anticipate, minimize, and respond to harmful discourse in ways that prevent violence while also protecting freedom of expression.

We advise several tech companies on their content policies, lending our research to answer questions on what to do about hate speech, violence against women, government troll armies, content regulation during elections, and inflammatory speech in countries at risk of significant intergroup violence.

- Promoting and protecting researchers’ capacity to study online content

We firmly believe that companies should collaborate externally to research methods of reducing harmful behavior on their platforms – and transparently publish the findings. To that end, we are founding members of the Coalition for Independent Technology Research, which is working to obligate companies to share their data for public interest research, protect researchers who independently collect data from companies, and establish best practices for ethical, privacy-protecting public interest research.

Phase 1 of the FFS (2020-2023) sought to investigate and reverse the “free speech recession” and work towards a resilient culture of free speech. The project met its objectives through research and advocacy activities, working with a range of stakeholders such as social media companies, states, international institutions, and civil society. The FFS wanted to investigate possible reasons for this recession, which is often attributed to authoritarian populism and its crackdown on dissent, civil society participation, and an independent press.

Phase 2 of the FFS (2023-2026) builds on findings of phase 1 and seeks to construct a framework through which free speech is promoted and adopted as an avenue through which negative online phenomena are to be curtailed. As such and in collaboration with the best-in-class institutions and organizations, we are developing speech protective measures (digital and analogue) to combat hatred, disinformation, and propaganda. So, rather than deflect from the fact that extreme speech can contribute to serious harm, the FFS focuses on exploring and promoting non-restrictive ways that freedom of expression and access to information can be used to combat hatred, disinformation and authoritarian propaganda in the digital age. One of the outputs that the FFS proposed is the current toolkit which aims at empowering internet users, online activists and civil society organization to use counterspeech as a central mechanism through which harms that come with the online agora of ideas and opinions are dealt with. In this light, it partnered with the DSP who, through their expertise and experience, have developed the content of this toolkit which will hopefully empower and inspire users to better understand and use counterspeech.

Further, in collaboration with the Vanderbilt Data Science Institute, the FFS is developing an Artificial Intelligence-based application which will allow users to promptly respond to online hate speech using counterspeech methods. This application, which is powered by large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT will allow users to upload an offensive post spotted online and generate a counterspeech response to the post in the user’s own voice. To set up and personalize the application, the app takes information from the user such as the user’s values and writing samples as well as a customizable collection of documents containing strategies for responding to hate speech. Additionally, the application will have access to a database of hate speech context, such as abbreviations and vocabulary used by extremist groups, which might otherwise be missed in an initial examination of the content. After this initial setup of the user’s preferences, the user can submit an offensive post and the application will draft a response to that post.

The goal is not to fully automate counterspeech, but to streamline and assist users in the process of drafting effective responses. The hope of this project is that it will ease the burden on counterspeech users in responding to the plethora of hate speech online today, as well as sustain free speech.

We therefore hope that the toolkit and forthcoming app will be beneficial for those who work on or who wish to work on using counterspeech to tackle online hatred.

To What Content Does Counterspeech Respond?

Counterspeakers make their own choices about which content merits a response, so their decisions are subjective and varied. Some groups of counterspeakers appoint a few members to select content to which the rest respond. In all cases counterspeakers themselves decide not only which content, but also which sources or authors to contradict. For example, some counterspeakers refute state propaganda, even though it sometimes puts them in danger of retribution from vengeful, powerful governments and/or their supporters.

When asked what content they look for, most of the counterspeakers the DSP has interviewed say “hate speech.” Counterspeakers also respond to other types of content, in all cases because they think it is harmful, including dangerous speech, disinformation, and terrorist content, which is itself a varied category. These types of content, all of which can overlap with each other, are explained below.

This is the most common term for objectionable content in English, and variations of the term are also used in other languages. Though there is no consensus definition for hate speech, all definitions describe content that denigrates or attacks people not as individuals but because they are part of some kind of human group.

Therefore if a child tells her mother ‘I hate you,’ that’s not hate speech because the emotion is directed at the mother on her own and in her own right, not as a member of any group. Also one would hope that the child’s emotion isn’t strong or durable to constitute hatred, though there is also no consensus on what exactly “hatred” means. “Hate speech” is very rarely codified or defined in law. The United Nations, in its Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech, offered this very broad definition, “any kind of communication in speech, writing or behavior, that attacks or uses pejorative or discriminatory language with reference to a person or a group on the basis of who they are, in other words, based on their religion, ethnicity, nationality, race, color, descent, gender or other identity factor.” There is no definition of hate speech in international human rights law. The United Nations notes that “the concept is still under discussion.”

Dangerous speech is any form of expression (including speech, text, or images) that can increase the risk that its audience will condone or participate in violence against members of another group. Some counterspeakers choose to respond to dangerous speech since it is a smaller, more objective category than hate speech, and since they see intergroup violence as an especially important harm to try to prevent. The #wearehere group of counterspeakers in Canada, for example, looks for dangerous speech and responds to it.

The idea of dangerous speech emerged after the DSP noticed striking similarities in the rhetoric that leaders use to provoke violence in completely different countries, cultures, and historical periods. One of these rhetorical ‘hallmarks’ or recurring patterns in dangerous speech is dehumanization, or referring to people in another group as insects, despised or dangerous animals, bacteria, or cancer. Rhetoric alone can’t make speech dangerous, though; the context in which it is communicated is just as important.

> For more information about #iamhere (which #wearehereCanada is part of), see the Examples section.

Both of these terms refer to falsehood. Disinformation is spread by people who know it to be false, and misinformation is spread by people who mistakenly think it is true, so the same content can be both dis- and misinformation, depending on who disseminates it. In any case it can produce significant, measurable harm. One prominent recent example is assertions that COVID was not nearly as dangerous as the vaccines against it. In response to such content, many people refused to be vaccinated and some of them needlessly died as a result. Another example is Russia’s assertion, before it invaded Ukraine in February 2022, that a major reason for the invasion was that Ukraine was being run by Nazis. Its President, Volodymyr Zelensky, is Jewish.

Counterspeakers often try to debunk disinformation and misinformation in hopes of protecting people against it by persuading them that it is false. The largest collective counterspeech group, #jagärhär or “I am here” in Swedish, which started in 2016, often organizes its members to counter hateful misinformation. In one case, comments under an article reporting that there had been several confirmed cases of bubonic plague in China was filled with remarks calling China a “contagious country” as well as many suggesting that it was the diets of Chinese people that caused the disease. In response, #jagärhär members wrote comments challenging the idea that the diets of Chinese people are uniquely dangerous, correcting misinformation about plague, and calling many of the comments in the thread racist.

> For more information about #iamhere, see the Examples section.

Terrorist and violent extremist content (TVEC) is a term used by some governments and tech companies to describe a variety of content that glorifies or promotes terrorism, and that may be used to recruit people as terrorists. New Zealand’s Department of Internal Affairs defines TVEC as “hateful or objectionable (illegal) material that promotes harmful extreme views such as:

- Articles, images, speeches, or videos that promote or encourage violence.

- Websites made by terrorist or extremist organizations.

- Videos of terrorist attacks and any other content that promotes violent extremism.”

Counternarrative is often used to try to undermine the content that extremist groups use to cultivate new members. In most cases, such counternarrative campaigns are designed to reach people even before they encounter TVEC online, so they will not be as susceptible to recruitment. One example is the animated counternarrative videos called Average Mohamed, whose main character is a Somali immigrant to the United States. In one example Average Mohamed asks “what do you think your job description is when you join Islamic State?” Then he answers his own question: kill, behead, and terrorize innocent people, destroy world heritage sites, and empower unelected and vicious people. “Not exactly Disneyworld…like the propaganda says it is, is it?” he says.

TVEC is prohibited on most online platforms and is often illegal in various jurisdictions, so when planning counterspeech and counternarrative strategies it’s important to keep in mind that the original content is likely to be deleted at some point.

Counterspeech Goals

When people choose to respond to hateful speech instead of just ignoring it, they often have a variety of motivations, and an overarching goal that they share with many other counterspeakers: to improve online discourse.

Many counterspeakers say that their posts and comments primarily target those who read hateful speech – the silent spectators – rather than those who write it. Some hope to change the views of spectators in the “movable middle” — people who read impassioned online discussions between people with opposing views, but don’t have strong beliefs on the topics themselves. Some counterspeakers also attempt to reach people who already agree with them but don’t yet dare to express those views online. Recruiting new like-minded counterspeakers would increase the amount of counterspeech, after all, and it’s easiest to do that without changing anyone’s views. Other counterspeakers (and some of the same ones) have another goal: to support people who have been denigrated or attacked by hateful speech. In doing so, they seek to mitigate the negative impacts of the speech on its targets. There are also counterspeakers who try to persuade those posting hateful comments to stop – either by educating them or by using social pressure tactics, such as shaming. Changing the mind or behavior of the original speaker with counterspeech seems to be more difficult than influencing the audience, but it is not impossible. In fact, online counterspeech has succeeded dramatically at it.

One well-documented example is that of Megan Phelps-Roper, who was raised in the insular, far-right Westboro Baptist Church that her grandfather had founded. Already as a teenager, she did all she could to spread his blistering hatred of homosexuality and gay people, and other dangerous speech from the church, including in a Twitter account that she started for that purpose. There, strangers’ online counterspeech slowly led her to question her ardent beliefs, until she left Westboro, was excommunicated by her family, and became a counterspeaker against her own former views. Phelps-Roper has published a book describing her experiences. In it and in a TED talk, she offers ideas for counterspeaking convincingly.

For more information about Megan Phelps-Roper, see the Examples section.

Strategies used in Counterspeech

Counterspeech takes many different forms, and counterspeakers use a variety of communicative strategies counterspeakers. Below, many of the most common or intriguing ones are described.

The most common response to harmful or objectionable content online – as to anything else offensive – is to try to get rid of it or wish that someone else would make it disappear. Some people are doing the opposite, though – drawing more attention to hateful or harmful content, by spreading it widely or by literally making it larger or more visible. The DSP has named this strategy “amplification.”

Those who use amplification in their responses often take conversations between a small number of people and post them in a much larger forum (online or offline) for many more people to see. This may seem counterintuitive: why create a larger platform for harmful or offensive speech when one’s ultimate goal is to reduce the amount of hate online?

Drawing the attention of a larger audience to bad content can be an educational tactic – for example, by showing men the type of harassment that women face online. Amplification can also oblige people to think about uncomfortable, important truths that they know, but don’t like to admit. For example the Brazilian counterspeech project Mirrors of Racism collected racist posts from social media and emblazoned them in large letters on billboards. A white Brazilian man who was interviewed just after he walked past one of the billboards said that people like him say their country isn’t racist, but the billboard demonstrated how false that is.

Second, when a piece of content is offered to a larger audience, it is very likely that at least some members of that new audience will not share the same speech norms as the original author. The new audience may react with counterspeech, reflecting their own norms.

> For more information about Mirrors of Racism, see the Examples section.

Some counterspeakers use empathetic language as a tool to change the tone of online discourse. They respond compassionately to those who post hatred, to try to connect with them and make them feel heard and understood. This can help change behavior or even beliefs. For example Dylan Marron, an actor, writer, and online content creator, reached out to readers who had sent him vicious and hateful messages, and invited them to speak with him by phone. When some of them accepted, he practiced what he calls “radical empathy” during the conversations, and presented those efforts in a series of podcasts and a book, both called Conversations with People Who Hate Me.

Counterspeakers also use empathetic language to reach out to people who are targeted by hostile speech online, and to establish norms of civil discourse in particular online spaces. To see that empathy-based counterspeech can produce dramatic transformations, one has only to look at the case of Megan Phelps-Roper whose beliefs and life were transformed by online counterspeech. She reports that the empathetic tone of some counterspeakers who engaged with her made all the difference. They reached out to her on a personal level, discussing topics like music and food. As Phelps-Roper describes:

“I was getting to know these people, and starting to feel like I was becoming part of this community, even though they were not close friendships. It wasn’t that I was consciously thinking ‘oh, I don’t want to offend these people,’ but it definitely became a feeling that I wanted to communicate our message in a way that they would hear. I came to care what they thought.”

Phelps-Roper cites this growing sense of community between herself and those responding to her as a primary reason why the counterspeech efforts were successful.

> For more information about Megan Phelps-Roper, see the Examples section.

Educational counterspeech occurs when people respond directly to a hateful or harmful message online in a way that provides the speaker or the audience with new information rather than merely publicizing their behavior to shame them.

In DSP interviews of counterspeakers, many said that educating people (either the person posting hatred or the audience) is their primary goal. Counterspeakers may correct hateful misinformation, explain why messages are hateful, or even amplify hateful speech as a method of educating others to its existence and the need for intervention.

A prominent example of this approach is Sweden’s #jagärhär (“I am here” in English) and its sister counterspeech groups in more than a dozen other countries. Mina Dennert, a Swedish journalist, founded #jagärhär in 2016 after she noticed a sudden spike in xenophobia and other hatred online, began responding to it, and then recruited others to help. She described the early days: “I used to talk to the people that followed the hate-bloggers and fake media sites asking them questions,” and giving them links to fact-checked information in an attempt to stop the ‘us-and-them’ rhetoric and help people that had been made to believe in the lies and were really scared and baited to hate immigrants, Muslims, and women. I started the group to get help from my friends to help me help people be free of their fears and hatred.”

> For more information about #iamhere, see the Examples section.

Some counterspeakers write humorous responses, for a variety of reasons. First, it draws readers, since most people love humor. It’s also a comfort to the counterspeakers, especially when they are responding to attacks on themselves. Hasnain Kazim, a German journalist whose parents immigrated to Germany from Pakistan, has been attacked for his name and skin color since he was a child, and has received torrents of hate mail as an adult. His humorous responses to hateful emails were a kind of coping mechanism for him, turning pain into fun. When he posted some of them on social media, they also won ardent fans who pleaded with him to write a book on the topic. He has written three so far.

“I often try to take it with humor, even if I don’t feel like laughing when I read the letters,” Kazim writes, referring to the hate mail he has received for years. “Humor is a way to cope with all the hate, to endure it, to bear it.” Humor is a good weapon against fear, he goes on to say, and then adds,” Ideally, humor is also a weapon against hate mailers, namely when it succeeds in hitting them, unmasking them or at least forcing them to think. This does not always work, but often enough, so that it is worthwhile to take this path. The important thing is to never hate back. Otherwise you’ve lost from the start.”

Members of Reconquista Internet (RI), an organized counterspeech group founded by German comedian Jan Böhmermann in 2018, also frequently use humor. The group was created to counter the hateful speech being spread by another group – Reconquista Germanica, (RG) “a highly-organized hate group which aimed to disrupt political discussions and promote the right-wing populist, nationalist party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD)”. Because RI group members were focused on a specific group of opponents, they sometimes used humor to annoy members of RI. “[We wanted to] ruin the internet for the people who ruined it for us,” said one member of RG, laughing. In one example, he described flooding a Discord server used by RG members with German idioms translated into English just “because it made us laugh.”

Humor may get someone who is posting hatred to change their mind, especially when they are the butt of the joke, but it can often attract attention or make counterspeech fun for those who do it, which in turn can make people more willing to keep counterspeaking over time.

> For more information about Hasnain Kazim and Reconquista Internet, see the Examples section.

Online shaming is commonly used to punish both online and offline speech or other behavior, and it always highlights discordance between one group’s norms and the behavior of someone else. Shaming ridicules someone, often in a large public forum, and serves as a warning to others of what can happen when someone breaks group norms.

An early, famous example of online shaming is the case of Justine Sacco. As the journalist Jon Ronson describes in his book, So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed (2015), in 2013, Sacco, a public relations executive, tweeted insulting remarks about people from several countries on a long trip, suggesting that the English have bad teeth, and that at least one German lacked deodorant. Then just before boarding a long flight to Cape Town, Sacco tweeted ”Going to Africa. Hope I don’t get AIDS. Just kidding. I’m white!”

By the time she had landed, tens of thousands of people had responded angrily to her tweet, and she was the number one worldwide trending topic on Twitter. Some corrected her (perhaps intentional) mistake, pointing out that white people could of course get AIDS. Outrage quickly grew into schadenfreude for some people, who eagerly waited for Sacco’s plane to land, so they could watch her learning of her own downfall. “All I want for Christmas is to see @JustineSacco’s face when her plane lands and she checks her inbox/voicemail,” one tweeted. They recruited a man in South Africa to go to the Cape Town Airport, take Sacco’s photo, and share it with the Twitter crowd that had quickly formed around the hashtag #HasJustineLandedYet. Sacco was soon fired from her job, among other tangible effects on her life. Many other people have also been fired after being shamed online.

Practical considerations

Before engaging in counterspeech, you should know of the risks involved. Counterspeakers are sometimes criticized and attacked for what they do. These risks are heightened for those who speak out against an authoritarian regime. If you are thinking of becoming a counterspeaker, it is important to learn how to protect yourself before you start.

PEN America, an NGO that works to defend freedom of expression, writers, and literature, produced Guidelines for Safely Practicing Counterspeech as part of a ‘field manual’ for dealing with online harassment. The guide recommends first assessing the threat, both in terms of physical and digital security. Safety risks depend on the context. Some factors to consider are: your location, to whom – and on what topic – you are responding, and how much of your personal information is available online.

The strategies you use in your response can also help protect you. Engaging alongside others can help, as it means you will not be a solitary target, and other counterspeakers can quickly support you if you are attacked online. Avoiding direct replies to an individual can also help avoid conflict. Instead, focus on counterspeaking in ways that can positively influence others who may be reading your comments – they are also the people you have a better chance of persuading. You can also ‘like’ counterspeech written by others.This amplifies their speech while limiting your personal exposure.

Examples

#iamhere is an international collective counterspeech network that was founded by Mina Dennert in Sweden in 2016. It has over 150,000 members and is active in 17 countries. Members work together through national Facebook groups to write, post, and amplify their counterspeech, which responds to comments on news articles posted on Facebook. Members follow a set of rules when crafting their counterspeech, which includes keeping a respectful and non-condescending tone and never spreading prejudice or rumors. To achieve their mission, #iamhere members search Facebook for hateful comments on news articles and public pages, and forward them to administrators who select a few for the entire group to refute. In a joint effort, members then post and like each other’s fact-based comments in the relevant threads. Capitalizing on Facebook’s ranking system, which prioritizes comments based on engagement (likes and replies), they can elevate their own civil responses and relegate others’ hateful or xenophobic remarks to the bottom of the threads where they are unlikely to be seen.

Members of #iamhere say they try to amplify comments that are logically argued, well-written, and fact-based, whether they are written by #iamhere members or not. The aim is to reach a broader audience, including those casually scrolling through their Facebook feeds, and to sway their opinions on the topic at hand. This persuadable group is often referred to as the “movable middle,” and #iamhere seeks to influence them with logical, factual counterarguments. Many members of #iamhere also counterspeak to let others know that they are not alone in opposing hateful speech. Comment sections can create an impression of widespread hatred, which isn’t necessarily representative of the majority. By sharing dissent and promoting a more constructive dialogue, they empower others who may have remained silent to express their viewpoints and join the conversation as fellow counterspeakers. #iamhere thrives on collaborative efforts and strategic utilization of Facebook’s platform to foster a culture of tolerance, understanding, and factual discourse. Through their dedicated actions, they endeavor to create a virtual environment where hateful rhetoric is drowned out, and the voices of reason and compassion prevail.

The Brazilian campaign Mirrors of Racism serves as a striking example of using strategic amplification to respond to hatred. In 2015, the journalist Maria Julia Coutinho (widely known by her nickname Maju) became the first Black weather broadcaster for the Brazilian prime-time news show, Jornal Nacional. This historic moment triggered a wave of racism online, with some Brazilians unleashing torrents of hate not only against Maju, but also other Black Brazilians.

In response Criola, a Brazilian womens’ civil rights organization, joined forces with the advertising firm W3haus to devise an anti-racism campaign. They decided to confront the issue head-on by gathering vivid and crude racist comments. These offensive statements were then plastered in enormous letters on billboards, strategically placed in five Brazilian cities in the neighborhoods where the offending individuals had posted the comments online. Each billboard also prominently displayed the comment, “Racismo virtual, consecuencias reales” (“Virtual racism, real consequences”).

“The strategy of the campaign was to take internet racism out of the internet and expose it in the streets so that the population (of the region) could become aware of the damage caused by these virtual acts,” said Criola’s General Coordinator, Lúcia Xavier. To further amplify the campaign’s message and content, W3haus conducted interviews with Brazilians regarding the campaign and shared the resulting videos. One video showcased the reactions of passersby on the street as they encountered the billboards. In this video, a middle-aged white man commented that some Brazilians tend to overlook the existence of racism, but the billboard effectively drew attention to this pressing issue. In another video, the person behind one of the racist posts stood in front of the billboard featuring his own offensive statement and blurred profile photo and apologized to a Black woman. These videos were then published online, which extended the campaign’s reach far beyond the communities where the billboards were situated, disseminating the anti-racism message widely.

For Hasnain Kazim, a German journalist who writes about topics such as refugee policy and the rise of the right-wing, populist Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) party in Germany, receiving hate mail is a constant source of pain. Although he was born in Germany and grew up in a small town there, people often assume because of his Pakistani name and brown skin that he is a foreigner, and send him furious messages telling him that he has no right to comment on German affairs. Most attack him as a Muslim (which he isn’t) and make hateful, often violent remarks about Muslims and Islam in general. Some ask questions to which Kazim responds, often at length. Unlike most counterspeakers who respond just once to each piece of content, Kazim engages in some extended dialogues with readers, sometimes painstakingly trying to educate them on topics like hijab-wearing or freedom of speech, and sometimes trading barbs.

In 2016, spurred by increasing xenophobia similar to what inspired Mina Dennert to start the counterspeaking group #iamhere, Kazim decided to respond to as many pieces of hate mail as he could manage, often humorously. He indeed replied to hundreds of messages. Although that task was both time-consuming and dispiriting, Kazim writes, he thought it was important to push back on the sort of vicious and violent hatred that’s often directed at him. “What scares me,” he writes, “is that I notice an erosion of resistance” to such hatred in German society. In one case, a reader identified only as “Christ2017” wrote Kazim to ask him, “Do you eat pork, Mr. Kazim?” “No,” Kazim replied. “I eat only elephant and camel. Elephant well-done, and I prefer my camel bloody.” “You want to be German, but you don’t eat pork?!” Christ2017 went on to call Kazim, without irony, an Islamist pig. “I didn’t realize that all Germans eat pork. Thank you for your clarification, now I know: pork is German Leitkultur! Woe betide anyone I meet at the next barbecue who doesn’t stuff a pork sausage in his mouth or is even, oh woe, worse than the worst Islamist, a vegetarian!” Kazim replied. Christ2017 then threatened him, “Be very quiet as an Islamist guest in our country!”

On at least one occasion, when the sender of violent threats included details of their profession, whether brazenly or accidentally, Kazim reported them to their employer. One such case happened in August 2020, after Kazim was told in an email that he should “first be really fucked up, then slit open and hung up by [his] intestines,” and that he was a “disgusting, dirty foreign parasite” who dared “to speak out against the proud German people”. The author was a sales representative at a German company and had sent the email from his work address. Kazim found his employer’s contact details and sent the content of the email to the company’s board, warning that unless action was taken against him, “a big deal” would be made of it. Some time later, Kazim was forwarded a copy of the man’s resignation letter. Kazim collected many examples of the hate mail he received, with his responses, and published them with extensive, thought-provoking commentary in a book called Post von Karlheinz (“Letters from Karlheinz”), in 2018. The book sold more than 100,000 copies. As of this writing, it had not yet been translated into English or other languages. Since then, Kazim has published two other books related to counterspeech including Auf sie mit Gebrüll! … und mit guten Argumenten (Go at them with a roar!…and good arguments) and Mein Kalifat: Ein geheimes Tagebuch, wie ich das Abendland islamisierte und die Deutschen zu besseren Menschen machte (My Caliphate: A secret diary of how I Islamized the West and made the Germans better people).

Reconquista Internet (RI) was started in late April 2018 by the German TV personality and comedian, Jan Böhmermann, who announced it during his popular satirical news show, Neo Magazin Royal. Böhmermann shared a link to a private Discord group in his Twitter account, attracting an astounding 8,700 members within the first three hours.

RI is unusual in that it was created to respond to content from one specific source: Reconquista Germanica (RG), a highly-organized hate group. RG disrupted political discussions and promoted the right-wing populist, nationalist party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD).

RI’s motto is “Wir sind nicht GEGEN etwas. Wir sind FÜR Liebe und Vernunft und ein friedliches Miteinander” (“We are not AGAINST anything. We are FOR love and reason and peaceful coexistence.”) Some members nonetheless stick to the initial call to action, which included a rather different motto: “We are the jerks who spoil the fun of the internet for the jerks who spoil the fun of the internet for us,” (“Wir sind die Wichser, die den Wichsern, die uns den Spaß am Internet verderben, den Spaß am Internet verderben.”) For them, “spoiling the fun” for the members of RG included many different types of responses, including such things as infiltrating RG’s Discord channels and flooding them with German idioms translated into English just “because it made us laugh,” said one member. But many RI members did follow the suggestion to “troll with love”, avoiding vitriol and hate in their responses. Joshua Garland and his colleagues studied the impact of RI on online discourse in Germany. They collected over 9 million tweets originating from RG and RI. The authors created a classifier to identify and code speech as hate speech, counterspeech, or neither. From 135,500 “fully-resolved Twitter conversations” that took place between 2013 and 2018, the authors found that after RI formed, the intensity and proportion of hateful speech apparently decreased. The authors note that “this result suggests that organized counterspeech might have helped in balancing polarized and hateful discourse, although causality is difficult to establish given the complex web of online and offline events and process in the broader society throughout that time” (p. 109).

When Megan Phelps-Roper was still a toddler, her grandfather Fred Phelps, a preacher who founded the tiny Westboro Baptist Church, became enraged that gay men were allegedly meeting for sex in a nearby park. In 1991 he sent church members to march in front of the park, carrying fiercely homophobic signs. They continued, daily, even after angry counter-protestors arrived.

As Phelps-Roper grew, so did the church’s new signature practice of picketing. She and her extended family marched all over the United States, including at the funerals of U.S. soldiers killed in Iraq and Afghanistan, to push Fred Phelps’ idea that the death of any U.S. soldier was a punishment from God against the whole country, for condoning homosexuality. As a teenager, Phelps-Roper created a Twitter account, and in 2009 started using the platform to spread Westboro’s hate. Her following grew quickly, but many people challenged her tweets, counterspeaking against the ideas she was trying to spread. Gradually, her adamant views changed.

Two types of messages were particularly effective at giving her doubts, Phelps-Roper said. First, people with religious knowledge and belief (including a rabbi) questioned the Westboro interpretation of the Bible. Among arguments with her ideas, she says that those that stayed within the territory of Biblical teaching were most likely to reach her. “Atheistic arguments were so far from what I could have done, so they weren’t as effective,” she said. Rather, it was those that “accepted the premises of my beliefs (the Bible), but then tried to find inconsistencies within it. That’s what opened the rest of it.”[1]

The second kind of message that influenced Phelps-Roper came from people who addressed her politely and tried to connect with her on a personal level, discussing topics unrelated to her own tweets, like music and food. She formed friendships with some of these people, and cites a growing sense of community between herself and those responding to her as a primary reason why the counterspeech efforts were successful. Rather than judging her beliefs and behavior against norms of a community of which she was not a part, the counterspeekers first tried to get to know her. Once she felt a sense of community with them, their norms started to hold meaning for her. In November 2012, she left the church.

Soon after leaving Westboro, Phelps-Roper decided to continue her work on Twitter. But rather than spreading hate, she dedicated herself to counterspeaking. Today she employs many of the same tactics that were once wielded against her: using factual arguments, trying to find common ground, and recognizing the humanity in other Twitter users.

In 2017 she gave a TED talk with guidance for counterspeakers, and in 2019, she published a book about her experiences called Unfollow: A Memoir of Loving and Leaving Extremism.

[1] Personal Interview, November 8, 2017.

Further Resources

Research and resources from the Dangerous Speech Project

- Counterspeech. Dangerous Speech Project. www.dangerousspeech.org/counterspeech

- Why they do it: Counterspeech Theories of Change by Cathy Buerger (2021)

- Counterspeech: A Literature Review by Cathy Buerger (2021)

- #iamhere: Collective Counterspeech and the Quest to Improve Online Discourse by Cathy Buerger in Social Media + Society (2021)

- Counterspeech on Twitter: A Field Study by Susan Benesch et al. (2016)

Other academic publications

- ‘Empathy-based counterspeech can reduce racist hate speech in a social media field experiment’ by Dominik Hangartner et al. in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2021).

- ‘Hate Beneath the Counter Speech? A Qualitative Content Analysis of User Comments on YouTube Related to Counter Speech Videos.’ by Julian Ernst et al. in the Journal for Deradicalization (2017).

- ‘Collective Civic Moderation for Deliberation? Exploring the Links between Citizens’ Organized Engagement in Comment Sections and the Deliberative Quality of Online Discussions’ (a study of #ichbinhier, the German #iamhere affliate) by Dennis Friess, Marc Ziegele & Dominique Heinbach in Political Communication (2021)

- ’Toxic Misogyny and the Limits of Counterspeech’ by Lynne Tirrell in the Fordham Law Review (2019).

Resources from other NGOs

- ‘Communicating During Contentious Times: Dos and Don’ts to Rise Above the Noise’ by Over Zero and PEN America

- ‘Best Practices’ and Counterspeech Are Key to Combating Online Harassment’ from the Anti-Defamation League (2016).

- Effective Counter-Narrative Campaigns, from Do One Brave Thing (2021).

- Guidelines for Safely Practicing Counterspeech, from PEN America’s Online Harassment Field Manual.

Facebook’s Counterspeech hub

Final Remarks

The Future of Free Speech thanks the below institutions for all their support in the creation of this output.

![]()

For more information on The Future of Free Speech please visit: https://futurefreespeech.org/

Media Inquiries

Justin Hayes

Director of Communications

justin@futurefreespeech.com